The internets, begins a gravitas-laden narration, are a series of tubes filled with cats.

https://flic.kr/p/7vnTcu

Or something like that.

Despite not being too clear on how it works (or compromises my privacy or threatens Western democracy), I love the internet and social media. I’m clearly addicted to the dopamine hits from all the likes, comments and retweets. I use the online sense of “community” to substitute for actual human interactions. I’m very lucky to have curated various feeds full of very smart people* (or maybe they’re bots?) who share information (articles, essays, videos) that proves interesting to me.

Some of them end up as fodder for more blog posts. Some I share for the amusement and edification of others! But most of all, they feed my dopamine habit.

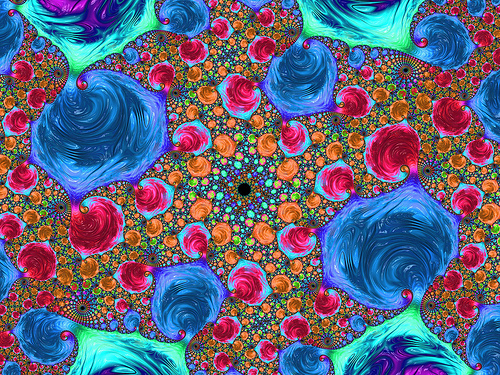

In Wired, Matt Simon compares the brain chemistry of human compulsive internet scrolling to how parasitic wasps zombify their insect hosts. The subjective sensation of this internet intoxication is akin to what psychologist Mihály Csíkszentmihályi describes as “flow.” Per Wikipedia,

flow is characterized by complete absorption in what one does, and a resulting loss in one’s sense of space and time.

I would argue there are few things more delicious that being so completely absorbed in something (a book, a task, etc) that you forget everything else around you. When you come back to yourself from a flow state, when you’ve knitted a sweater or finished a novel or eaten an entire bag of that Chicago-style popcorn, you at least feel like you’ve

accomplished something! With the internet, though, there are just miles and miles of scrolling (and hitting “reload” on your analytics page) left before one can sleep.

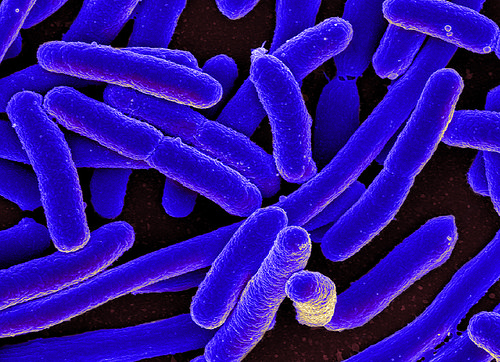

Not only is the pleasure of internet madness illusory: Most likely, so are the “people” I encounter and the clicks and comments they make on my site. In New York Magazine, Max Read describes how much of what we think of as the Internet (traffic, clicks, retweets) is fake, generated by spam-bots and click-farms.

Does it really matter that spam-bots are the largest part of my appreciative audience? Normally, spam comments are mostly gibberish with some suspicious links. Akismet is excellent at flagging them and I take great enjoyment from reading (and deleting) them from my spam queue. Recently, however, I have received several “Flatter-bot” messages in my spam queue that are more cogent than usual, leaving compliments or asking for advice.

Khalil writes, “Admiring the time and energy you put into your site and in depth information you offer. It’s nice to come across a blog every once in a while that isn’t the same out of date rehashed information. Wonderful read! I’ve bookmarked

Corinne says, “I am really enjoying the theme/design of your site.

Do you ever run into any web browser compatibility issues?

A small number of my blog readers have complained about my site not operating

correctly in Explorer but looks great in Firefox. Do you have any advice to help fix this issue?”

Jim exclaims, “Greetings! Very useful advice in this particular article! It is the little changes which will make the largest changes. Thanks a lot for sharing! I couldn’t refrain from commenting. Exceptionally well written! I’ll immediately

take hold of your rss feed as I can not to find your email subscription hyperlink or e-newsletter service. Do you’ve any? Please permit me recognize in order that I could subscribe.”

Aww, thanks, Flatter-bots! Maybe I’ll keep you after all.

Tangents:

AI Researcher Janelle Shane trains neural networks to generate names for cookie recipes, guinea pigs and paint colors, with very entertaining results.

I’m not sure if this is akin to how bots generate comment spam, but it would certainly be more entertaining that random sketchy links or personal attacks.