In Ursula Le Guin’s Earthsea stories, knowing a person or animal or object’s “true name” gives a wizard power over him or her or it. Therefore, humans (and other sentient beings, like Dragons) take particular care to avoid sharing their true names with others, lest they be compelled by a power-hungry wizard.

I first learned about Linnean taxonomy, and the practice of classifying organisms by binomial nomenclature (e.g. Homo sapiens) in my middle school science classes. This was also about the same time I was reading the Earthsea books. Not surprisingly, these two concepts, The Rule of Names and the taxonomy of biological naming, remained linked in my mind for a long time.

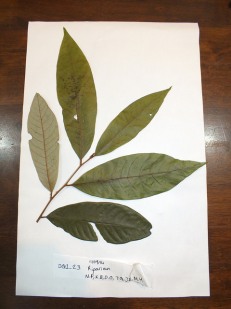

- My field notebooks looked sort of like this. DG_1_023 Myristicaceae by Aber TREC, (2014) CC By-NC 2.0, on Flickr https://flic.kr/p/py7Eae

In my field science courses in college, I was an omnivorous species identifier. Samples of Sonoran desert plants (well, the ones that would smush flat) made their way into my field notebooks, with carefully labeled common and scientific names. With each new named species, it felt like I was slowly mastering control over my unfamiliar environment. If only I could learn all the names, I would know everything about the ecosystem.

When I got to TEVA, teaching environmental education, I was surprised that we were discouraged from telling kids an organism’s names (common or scientific) outright in response to the question, “What is that?”

Instead, of answering with “Oh, that’s an Eastern Hemlock (Tsuga canadensis,)” our training was to turn the question around to the kids.

“What do you notice about it? What about its color, smell, or texture can you describe?”

The best part was that kids would come up with their own names for plants based on their observations and continue to identify them for the rest of the time we were on the trail. For example, Eastern Hemlock became “Dragon Tree” (because of its large floppy wing-like branches and white-striped scales). It was only later that we told them the “real” names of the organisms, or let them look them up in a field guide by characteristics.

Some of my favorite names students came up with were Bubble Gum Slime (aka Lycogala epidedrum – a pink slime mold); Smurf Caps (aka Lactarius indigo – a mushroom that oozed blue goo); Ghost Roses (aka Monotropa uniflora – a flower-like bleached white plant); and Velcro balls (aka Arctium minus – burdock seedpods covered with tiny hooks that snared hair and clothing.)

Had we told them the “real” name outright, the kids would have heard a name and promptly forgotten it. Maybe even thought that the label encapsulated everything you could know about the organism. We would have missed a tremendous opportunity for kids’ exploration and engagement with the natural world.

Most recently, I get my nature fix by going on walks outdoors here in Michigan. Sometimes, if I see something that I haven’t seen before, (or that just looks really cool), I take out my cell phone and snap a picture with the camera. I could (and often do) look up the species in a field guide. I also started uploading my photos to the site iNaturalist, to source community identifications for my observations. By adding my photos, with dates and geographic data to the online database, it provides a record that other members can refer to. It’s a resource for researchers and a form of participatory citizen science.

I also have been learning to identify new species from the system, as well as tagging “Unknown” photos with high level identifications (i.e. “Plant” or “Fungi”) in order to make the photos more widely searchable to community members who can provide more detailed identifications. It’s a form of social media in some ways as addictive as Facebook or online dating sites (but instead of rating pictures of potential dates, I attach a label if I think it’s a vertebrate.) There is also definitely a serotonin hit when other members agree with your identification, or provide additional comments on an observation that is as potent as the “FB like” button.

I wonder (dubious seratonin hits aside), if I am I reverting to an earlier understanding of “Name *ALL* the things” vs. a more nuanced engagement and exploration of the natural world. Sure, the site has leaderboards to track which members have made the most identifications or posted the most observations. Is it a competition ala a birder’s Big Year or just creating a sense of order in a chaotic and messy world? And are either of these appropriate forms of interacting with nature? What about if they are tempered by the sense of wonder and Radical amazement that I feel on my walks, or looking at pictures of really, really cool organisms?